During the mass migration beginning in the 1880s and continuing up to the Great War that saw millions of Italians emigrate to South America and the United States, a small but significant migration pattern entered Canada. Despite the Canadian governments preference for immigrants from northern Europe to settle and farm the Prairies, Italian workers still could be found all over Canada doing backbreaking seasonal work. Labour recruitment programs established by such major Canadian companies as Canadian Pacific Railway, Canadian National Railway and Dominion Coal Company brought workers in as almost chattel labour to work on railway construction, clearing bush in Canada's hinterland or engaging in other forms of manual labour. Between the years 1901 and 1911 almost 2 million Italians arrived in the United Sates as compared to a the only 60,000 who came to Canada. In the minds of Italian migrants at the time the boundary between the two countries was irrelevant and many more may have just crossed into Canada following work opportunities and kinship chains. They were going to fare l'America to make a better life for themselves and their families.

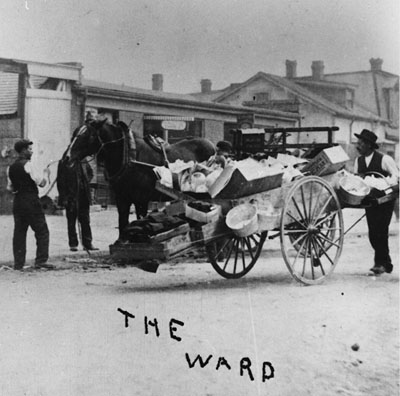

1910-1924 Italians begin to establish neighborhoods with an Italian ambiance in Canada's major urban centres. "The Ward" in Toronto's downtown develops a small community as seasonal workers in Ontario's hinterland settle in the city during the winter.

At first, settlements of Italians in Canadian cities tended to be predominantly male seasonal workers who returned to the cities after working to clear brush, set rails, or mine. Gradually as Toronto and other cities addressed the need for the urban infrastructure of sewers and trolley lines Toronto's Italian population grew and settled more permanently.

By 1910 sojourners were settlers working as stonemasons, tailors, bricklayers, and cobblers. Toronto contained several neighbourhoods known as "Little Italies" during this early period. The most important were first, the area around College and Grace Streets, second, Davenport Avenue and Dufferin Street and third, the Ward in the downtown bounded in the south by Queen Street (see map) where today Toronto's city hall and the hospitals on University Avenue are located.

1924-1947 THE INTER WAR YEARS

1924 Italy restricts emigration.

Canada restricts immigration.

During the 1920s and 1930s immigration restrictions and regulations encouraged by racialist and xenophobic notions in Canadian public opinion and politics limited South European, hence Italian immigration. At the same time, fascist government policy in Italy viewed continuing, large-scale emigration as a national embarrassment. The Italian authorities enacted laws in 1924 and 1929 to impede Italian emigration. These legal changes and effects of the depression halted Italian immigration to Canada until after the Second World War.

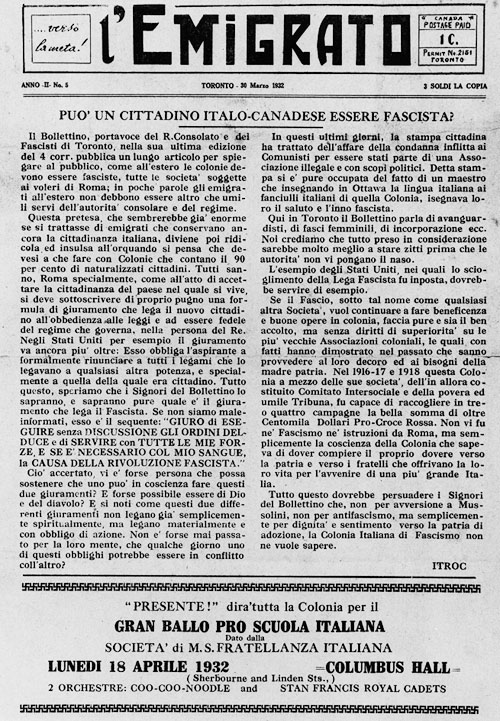

The British and Canadian press, governments and much of public opinion looked favourably upon Mussolini's regime at first. While opposition to the Mussolini regime existed among some of Canada's Italian population, others joined in patriotic events, clubs and associations, since it appeared that Mussolini might bring stability and prosperity to Italy as well as international recognition and respect. But, Mussolini's aggression in Ethiopia in 1935 and other bellicose actions, turned public opinion in Britain, Canada and the United States. Italian Canadians themselves debated whether they could be both Canadians and Fascists.

1940 Over 700 males of Italian origin interned at Camp Petawawa.

Italian Canadians discovered that loyalty to two nations left them in an precarious position when war developed. Hundreds of males of Italian origin were rounded up as "enemy aliens" and interned at Camp Petawawa by Canadian authorities. Those arrested were denied their rights to habeas corpus. This denial of civil liberties extended not just to known Fascist sympathizers but to all enemy aliens even those who were of Italian origin but had become naturalized British subjects. Those not interned were required to register with local police.

1947 Removal of the Enemy Alien Act in 1947 allowed Italians to migrate to Canada once again.

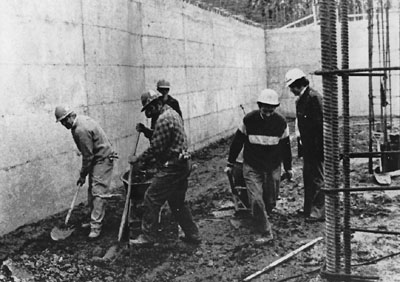

After 1945 when Canada's heavy industry, construction and manufacturing sectors required labour, Canadian authorities continued the traditional racialist preference for northern European immigrants to meet the country's demands. But, it soon became evident that southern Europeans were more likely to wish to emigrate to Canada. Old chain migration networks to Canada reopened and new ones began. Many Italian immigrants in Toronto began work as labourers or artisans in the expanding construction industry

1951-1970 The arrival of large numbers of Italians creates a critical mass for the ethnic community. Commercial areas and residential zones develop an Italian ambiance.

Between 1951 and 1961, Canada's Italian population increased fourfold from 150,000 to 450,000. Older Italian settlements were quickly overwhelmed by the new arrivals. Throughout the 1950s, over 20,000 Italian immigrants entered Canada annually. These numbers began to drop sharply by the early 1970s. Between 1946 and 1983 it is estimated that between 433,159 and 507,057 Italians came to Canada.

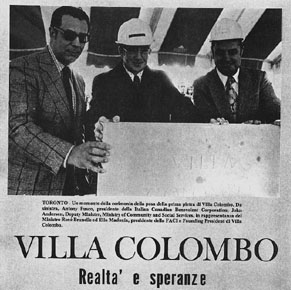

1976 Italians in Toronto build an home for the Aged called Villa Colombo.

By the 1970s many Italians in Toronto discussed the idea of creating a social centre and home for seniors. In response to the growing number of elderly people of Italian origin in the city a group of business people, social workers and community activists organized an effort to build a Home for the Aged. As the project developed, it became a focal point for community events. Attached to the care facility for seniors was a banquet hall and indoor piazza. This architectural style was chosen to ensure that different generations interacted at one central place in Toronto. Villa Colombo became the destination for Canadian and Italian dignitaries when they wanted to speak to issues that would effect people of Italian origin.

1979 Italians face bigotry and stereotypes in the English-speaking media.

Throughout the years that Italians have faced demeaning stereotypes regarding their connections criminal activities. Some Italians changed there last names to avoid the bigotry they confronted in the workplace or in neighborhoods. The spectra of the mafia has an alluring image for non Italians. Even if research shows Italians to be as law abiding as any other group in Canada, Italophobia still is apparent in the media and in the everyday interactions in public culture. Newspaper and television reports filled with innuendo and distortions accompanied the economic success Italians achieved through hard work and labour in the construction and manufacturing industries. Part of the effort to build places such as Villa Colombo and Columbus Centre, an adjacent community centre, was to offset the negative images portrayed by English-speaking institutions.